If there’s anything people are good at, it’s retrofitting events with a coherent narrative. Even, or maybe especially, when the ultimate causes of past events are the forces of chance. If you look closely you can see this everywhere.

Ancient examples abound. In Moralia, Plutarch relates an incident in which a vestal virgin was struck by lightning and killed. Although this is the definition of randomness to our ears, to the Romans this was an event of profound significance. Clearly, some sin of the surviving virgins was yet uncovered, and in time several were duly convicted of illicit offenses. Punishment for this, by the way, usually involved the offenders being buried alive. Not quite confident that they had set the universe right again, the Romans consulted their Sibylline books (for a contemporary analogue, consider Nostradamus or the Bible Code). Having done this, for good measure, they elected to also bury two live Gauls and two live Greeks.

The modern reader might be tempted to chuckle at this display of superstitious lunacy. But I don’t think we should be so confident that we’ve conquered this species of irrationality. It would be much too depressing for me to go on at length about the case of Cameron Todd Willingham. “Comedy equals tragedy plus time,” they say, and while ancient cruelty fits the bill, Texan cruelty doesn’t.

So let me hastily change gears and point out that a large percentage of CNBC programming is a more benign manifestation of this kind of thinking. The stock market never fluctuates up or down on a given day, the stock market sinks or rallies for a reason. And that reason invariably involves the actions of heroes and villains. One article pulled out of a hat reveals arcane symbology and slapstick levels of claimed precision:

A classic bearish head and shoulders pattern seems to suggest that further declines may be ahead. For this scenario to occur the Dow Jones will need to see a break below 12,471 to confirm we are heading lower.

And if you want another example, go check the Facebook profile of every ostensibly-atheist Brooklyn asshole you know the next time Mercury is in retrograde.

There is a school of thought in biology—and don’t ask me how widely this is accepted—that evolution favors Type II errors (“failing to reject a falsehood”) over Type I errors (“failing to accept a truth”). The argument goes like this: while there’s not much immediate consequence to believing that your dancing caused the rain, there is probably a lot of selection pressure working against animals that can’t make the connection between hearing a rattle and being bitten by a snake. This eminently practical adaption misfires in our present situation, and that makes us susceptible to the category of cognitive bias I’ve been describing. We are prone to find meaning in everything. Add a dash of salt, stir, let simmer for a millennium or two and you get the Catholic Church. Please note that I like to repeat this sermon at every opportunity, since it makes such a good story.

Practical Consequences

I am going somewhere with this, of course. For those of us attempting to do something resembling science on the web, a keen awareness of this tendency is crucial if we are to do our jobs well.

To illustrate what I mean, let me show you some real and recent Etsy data. I ran an A/B test on Etsy search pages for a while, and then I poked around to see what metrics had changed with 95% confidence or better. Here’s what I found:

| Action | A | B | Change | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Followed | 0.55% | 0.59% | -7.4% | 0.022 |

| Registered | 0.46% | 0.42% | +9.0% | 0.022 |

| Homepage | 51.4% | 51.1% | +0.48% | 0.049 |

| Item page | 72.7% | 72.5% | +0.31% | 0.044 |

| Action | Group A | Group B | Change | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Followed another user | 0.55% | 0.59% | -7.4% | 0.022 |

| Registered | 0.46% | 0.42% | +9.0% | 0.022 |

| Viewed homepage | 51.4% | 51.1% | +0.48% | 0.049 |

| Viewed a listing | 72.7% | 72.5% | +0.31% | 0.044 |

Given this, we can try to piece together what happened.

We can see that while fewer people in group A followed another user, many more signed up for Etsy. (This is a very interesting result, because we know that at least half of people register in order to purchase.) We also find that fewer people in group B ever managed to look at an item on Etsy. So the result seems to hint at a fundamental tradeoff between social features and commerce. We can encourage engaged users to follow each other, but this is a fringe activity, and it will put off people that show up on the site to buy things.

Right? No. Completely wrong. What I neglected to explain was that this A/B test does nothing. It randomly assigns visitors into group A or group B, and nothing else. Any changes that we observe in this A/B test are, by definition, due to chance. But that didn’t stop me from telling you a story about the result that I think was at least a little bit convincing. Imagine how well I might have done if we were measuring a real feature.

The statistical mistake I’ve just made is to fast talk my way past “95% confidence” and to hide data. If we’re 95% confident of a change, then we’re 5% unsure of a change. Or to put it another way, one metric in twenty that we measure like this will be wrong. I had about a hundred metrics, and I cherrypicked four whose changes were calculated to be statistically significant.

From there, the flaws in my own software could take control and explain why this data shows that the virgin was struck by lightning because the goddess of the hearth is pissed about unchaste behavior within her sacred temple and in order to rectify this situation, we have to throw some hapless barbaris in a pit. Obviously.

Binding Oneself to the Mast

So to bring this meditation to a close, let’s reflect on how we can reduce our chances of making these mistakes. Well, first, we have to realize that by our very nature we are struggling against it every day. Check. And when our enemy is ourselves, one of the most effective countermeasures known is a Ulysses contract.

After investing some time into building a feature and testing it, we know that we’re going to have some level of emotional involvement in it. We’re only human. If we can identify specific tendencies that we’ll have in our less sober moments, we can drag ourselves back to honest assessment. Kicking and screaming, if necessary.

- We may be tempted to cherrypick numbers that look impressive and appeal to our biases.

- We are prone to retrofit a story onto any numbers we have. And we will believe it, even if intellectually we understand that this is a common mistake.

We can address these problems with tooling and discipline.

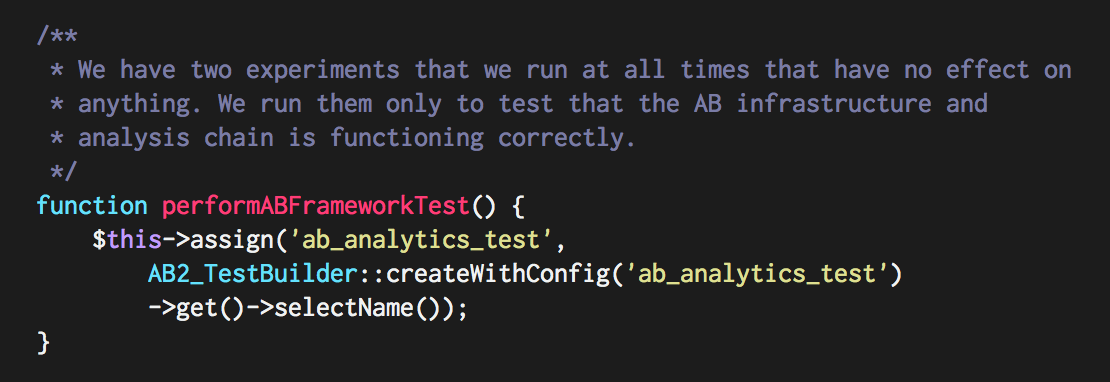

First, we can avoid building tooling that enables fishing expeditions. Etsy’s AB analyzer tool forces you to reveal each metric that you think might be worth looking at one at a time. There’s no “show me everything” button. Now, this may have arisen entirely by accident and laziness, but it was for the best.

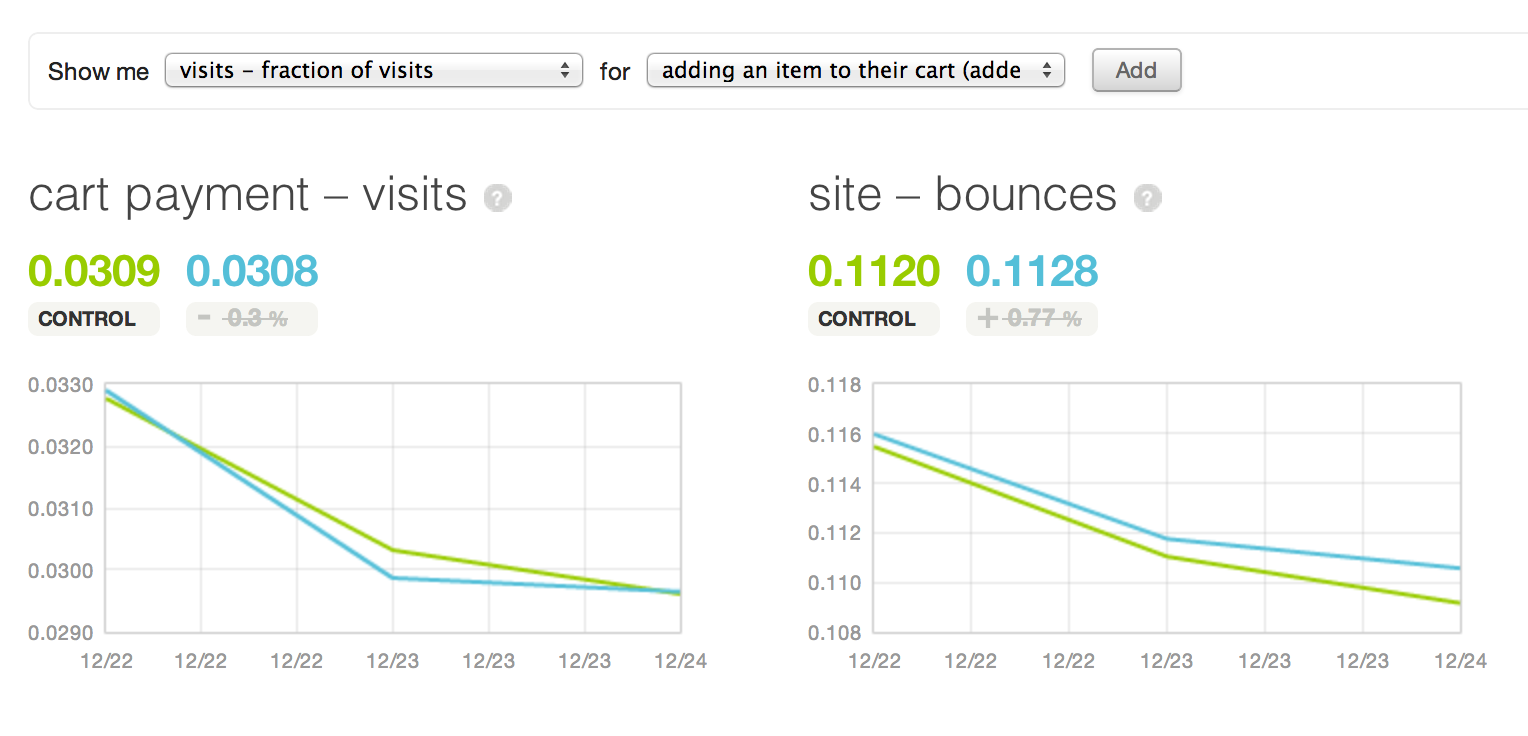

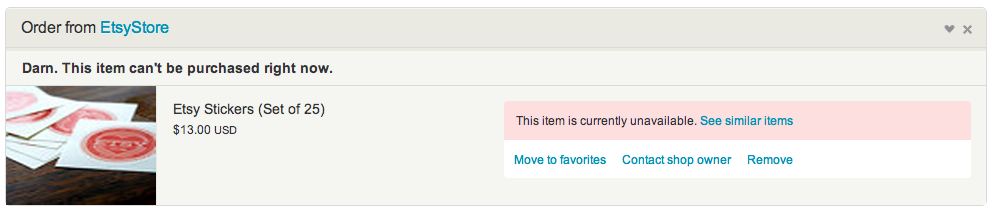

Second, we can limit our post-hoc rationalization by explicitly constraining it before the experiment. Whenever we test a feature on Etsy, we begin the process by identifying metrics that we believe will change if we 1) understand what is happening and 2) get the effect we desire. A few months ago, we ran an experiment suggesting replacements for sold or unavailable items still in user carts.

The product manager wrote the following down at the time of launch:

We expect this experiment to reduce dead-ends on the site and to give cart visitors an avenue for finding replacements. We expect an increase in listings viewed, a decrease in exits from the cart page, and an increase in items added to carts.

Listing a combination of several expected observations is key, since every prediction reduces the odds that this will happen entirely by random chance. If the experiment results in the expected changes, we can have a high degree of confidence that we understand what is happening.

Humans are at once flawed and remarkable animals. Much as we might imagine ourselves to be rational actors, we aren’t. But we can erect frameworks in which we can compel ourselves to behave rationally.